Increasing Housing Density: What D.C. can teach us about “gentle density”

Hourglass Lancaster

This article ran in the Summer 2021 issue of Hourglass Quarterly. View the full publication here.

Lancaster County is not building at the density outlined in Places2040, which is 7.5 units/acre. One challenge for building at a higher density is zoning. Another is misconceptions from neighbors that dense housing will change the character of their neighborhood, increase traffic, or other issues. What can Washington, D.C. teach us about tackling this challenge? A Brookings Institute Report.

On roughly 75% of land in most cities today, it is illegal to build anything except single-family detached houses. The origins of single-family zoning in America are not benign: Many housing codes used density as a proxy for separating people by income and race. But as communities across the U.S. grapple with worsening housing affordability, there is growing interest in how zoning rules could be relaxed to allow smaller, less expensive homes.

Often, the choice is posed as a trade-off between detached homes with big yards or skyscraping apartment towers. In reality, the housing stock in most communities is much more diverse than these two extremes. While high-rise apartments in strategic locations should be part of the solution, many single-family neighborhoods could easily yield more housing—and more affordable housing—if land use rules allowed “gentle” increases in density, such as townhomes, two- to four-family homes, and small-scale apartment or condominium buildings.

A D.C. example

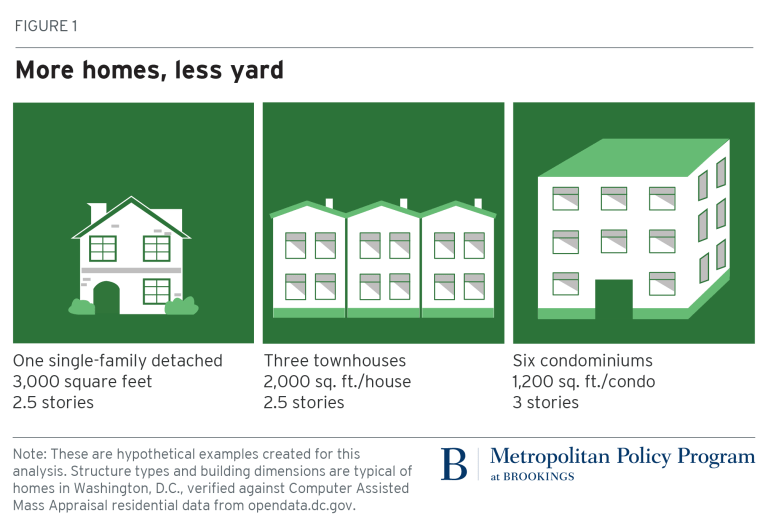

Washington, D.C. has several predominantly single-family neighborhoods close to downtown that would offer perfect opportunities for gentle density. According to tax assessor data, the median lot size for single-family detached homes in the District is 5,460 square feet, compared to 1,600 square feet for rowhouses and 4,100 square feet for four- to six-unit multifamily buildings. This suggests that most single-family lots could accommodate more housing. The figure below shows some different scenarios for a 4,500 square foot lot, currently occupied by a two-and-a-half-story, 3,000 square foot single-family home including: the lot as is, redeveloped with three side-by-side townhomes, or redeveloped with a three-story, six-unit condo building.

According to analysis from the Brookings Institute, the newly built townhomes would sell for nearly the same price per unit as the current single-family detached home (assuming that single-family homes that are most attractive for redevelopment are in poor condition and buyers who purchased the home to live in rather than redevelop would likely incur substantial renovation costs.)

In the other redevelopment scenario, the per-unit prices for a six-unit condominium building are about 40% lower than for the three townhomes. One important factor is that the land costs, expensive in D.C., are divided among six completed homes, rather than three. The second reason the condo prices are lower than townhomes is that each unit is smaller: 1,200 square feet per condo versus 2,000 square feet per townhome (typical sizes in the District for each structure). This analysis shows that adding more homes in single-family neighborhoods makes it possible for more people to move into the neighborhood and that under certain conditions, the new homes will also improve affordability.

Density supports neighborhood retail and a healthier planet

Adding more homes—and thus more neighbors—to low-density neighborhoods can help support local retail businesses that depend heavily on foot traffic, like hardware stores, bakeries, and restaurants. Although dense housing reduces yard space, good landscaping, green roofs, and other design solutions including sidewalk berms can offset stormwater runoff. Local retail that households can access without driving helps reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the largest driver of climate change and air pollution. And with good planning, increased density in single-family neighborhoods won’t necessarily mean more cars competing for street parking.

More homes equals more affordability and economic opportunity

The D.C. redevelopment scenario offers three main lessons for policymakers thinking about how to improve housing affordability.

First, it is possible to add more homes in single-family neighborhoods while keeping buildings at similar scale. When viewed from the street, three adjacent townhomes or six small condos can be constructed at approximately the same height and mass as existing single-family homes.

Second, allowing smaller homes that use less land is an important way to improve affordability. Where land is expensive, adding more homes on a given parcel reduces housing costs for each household. Gentle density also enables better matching between the size of one’s house and the size of one’s household; Washington, D.C. has seen rapid growth of one- or two-person households, many of whom would prefer to live in small apartments. Where these are not available, they end up sharing single-family homes or apartments with multiple households to reduce costs. Building more small homes—including accessible flats for older adults—would free up the existing single-family stock for people who need larger homes, including families with children and multigenerational households.

Third, diversifying the housing stock in exclusive neighborhoods creates better access to economic opportunity. The reason land is expensive in these neighborhoods is because they are located near job centers and transportation hubs, and offer amenities such as excellent public schools and low crime.

Removing barriers to townhomes, two- to four-family homes, and small-scale multifamily buildings can be part of the solution to communities like ours that need more housing, especially low-cost housing.

Related Articles

Blog topics cover everything from research and statistics to opinion pieces. Stay informed and keep reading for more.